What we lose when machines begin to create for us

When we say a product is handmade, we imply craftsmanship and care—artisanship shaped by intention. A handmade product may not have the polish or perfection of something machine-made, but its flaws reflect a beauty imbued by the soul of the human hands that formed it—something a soulless machine can never impart.

As artificial intelligence (AI) seeps ever deeper into our world—especially into domains once considered exclusively human, like writing—we’re witnessing not just the disappearance of products made by hand, but creations born of the human mind.

Are mindmade creations disappearing too?

Is AI overtaking creations from the human mind in the same manner as industrialization overtook products of the human hand?

Childhood and the Meaning of Imperfection

As a child growing up in the 1970s, I didn’t yet understand the value of handmade things. I remember my mother’s excitement when something was labeled “handmade,” but I couldn’t see what she saw. To my child’s eye, the imperfections stood out—the slight discolorations, the asymmetry, the out-of-bounds brushstrokes, the inconsistent measurements. These seemed like flaws, not features.

But with age, I began to understand. Those flaws weren’t defects—they were signatures. They gave each object a unique personality and embodied the presence of the maker. The irregularities whispered that a person, not a machine, had been here. They made the product human.

Movie poster of “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=85715937

In It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart) is repeatedly annoyed by a loose decorative knob that falls off his staircase railing. But after his transformative revelation—that his life, however messy, is meaningful—he embraces that broken knob with joy. It becomes a symbol of everything he now cherishes: the imperfect, beautiful reality of his own existence.

Much like George Bailey, I eventually came to understand my mother’s love for handmade things. They are more than just objects. They are evidence of dreams, flaws, and humanness.

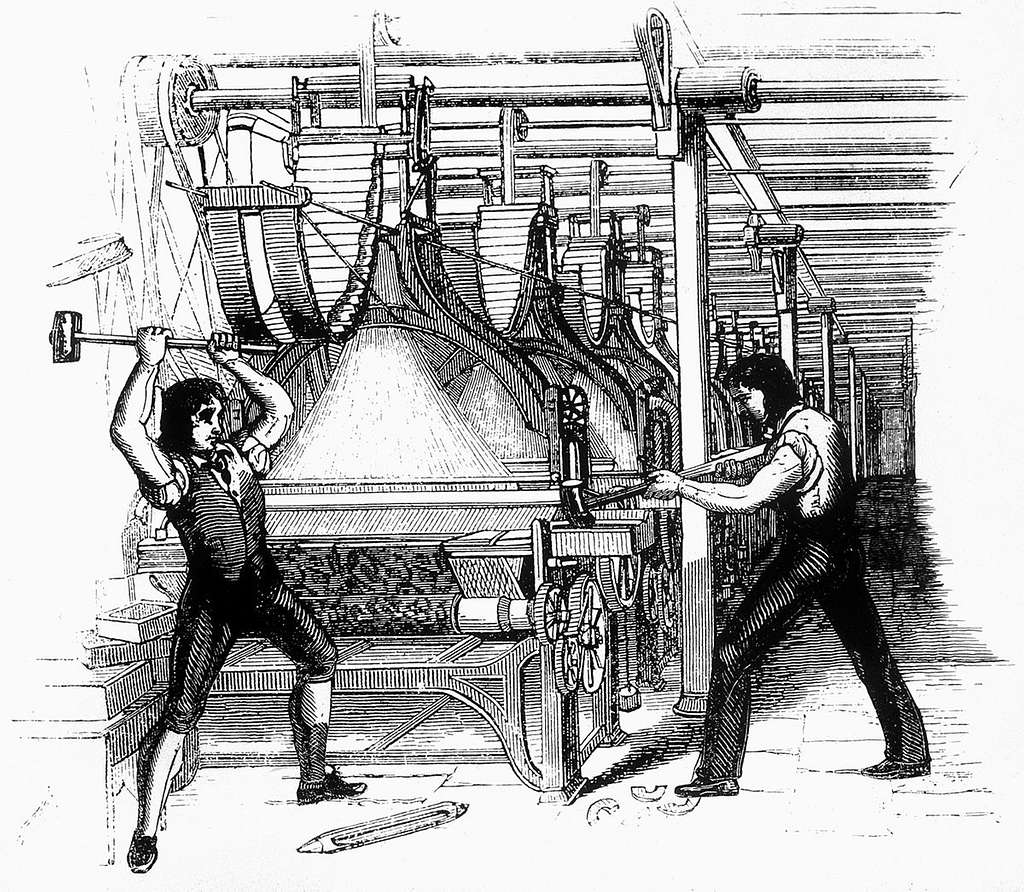

Luddites and Looms

Of course, the fear of machines replacing human effort is nothing new.

The computer age displaced many labor-intensive jobs. The Industrial Revolution replaced backbreaking labor. Cameras replaced portrait artists. The printing press rendered calligraphers obsolete.

Frame-breakers, or Luddites, smashing a loom. Machine-breaking was criminalized by the Parliament of the United Kingdom as early as 1721, the penalty being penal transportation, but as a result of continued opposition to mechanization the Frame-Breaking Act 1812 made the death penalty. Public domain

In the early 19th century, the Luddites—textile workers threatened by industrial looms—took up arms (literally) against automation. Their name came from the possibly mythical figure “Ned Ludd,” who symbolized resistance to mechanization. The Luddites smashed looms, sabotaged factories, and protested the erasure of their livelihoods. Their story has since come to symbolize futile resistance to inevitable progress.

But was it so futile?

Today, we don’t lament the end of hand weaving—but we do value handcrafted textiles. We pay extra for artisanal goods. We marvel at handwritten letters. We buy handmade pottery, knitwear, and woodwork not because they’re perfect, but because they’re personal.

Mindmade in the Age of LLMs

Now we stand at a similar inflection point—this time not with our hands, but our minds.

As a member of a writers’ guild, I’ve seen the debates firsthand. Some writers are cautiously optimistic about AI’s role in writing. Others see tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Copilot as existential threats to creativity itself.

Large language models (LLMs) can produce passable prose in seconds. They can mimic tone, summarize arguments, and even write poetry. Does this mean the art of writing—of expressing something ineffably human—is under threat?

We should consider a new term “mindmade,” like handmade, to reflect creations from human thought as opposed to AI algorithms.

Maybe. But maybe not.

Just as industrialization pushed craftspeople to become artisans, AI may push writers to become something more than content creators. We may begin to value writing not just for what it says, but for who says it—and why. That’s where the term mindmade comes in.

If handmade means formed by human hands, mindmade should mean formed by human thought—by intuition, imagination, memory, and soul.

Toward a New Kind of Craft

We must stop treating the arrival of AI as a zero-sum game. Yes, AI will write emails, memos, reports, and maybe even marketing copy. It will take on much of the mundane writing we’ve long been burdened with. Will we really miss those?

An AI-generated image summarizing the essence of the blogpost.

Rather than mourn the tasks we lose, we should elevate the ones we keep. Let’s treat mindmade writing like handmade pottery or calligraphy—something uniquely human, with all its rich textures and idiosyncrasies. Let’s value it for the same reason my mother cherished her handmade items and George Bailey loved his broken banister knob: because it was real.

In a world increasingly defined by algorithmic perfection, our imperfections may be the most valuable thing we have left.

So let the machines write what they must. But let us write what only we can.

Disclosure. This article was originally written by David Page, but ChatGPT revised and update the text.