We live in a world that remembers everything. Our smartphones double as ever-watchful eyes, recording, archiving, and sharing our every move. The digital age has granted us something close to perfect recall, a kind of modern-day Eye of Providence—not divine, but relentless.

But what if forgetting is essential for understanding? What if the ability to forget is what allows us to truly know?

Welcome to the Luria Paradox: the surprising notion that perfect memory doesn’t enhance knowledge—it cripples it.

The Man Who Couldn’t Forget

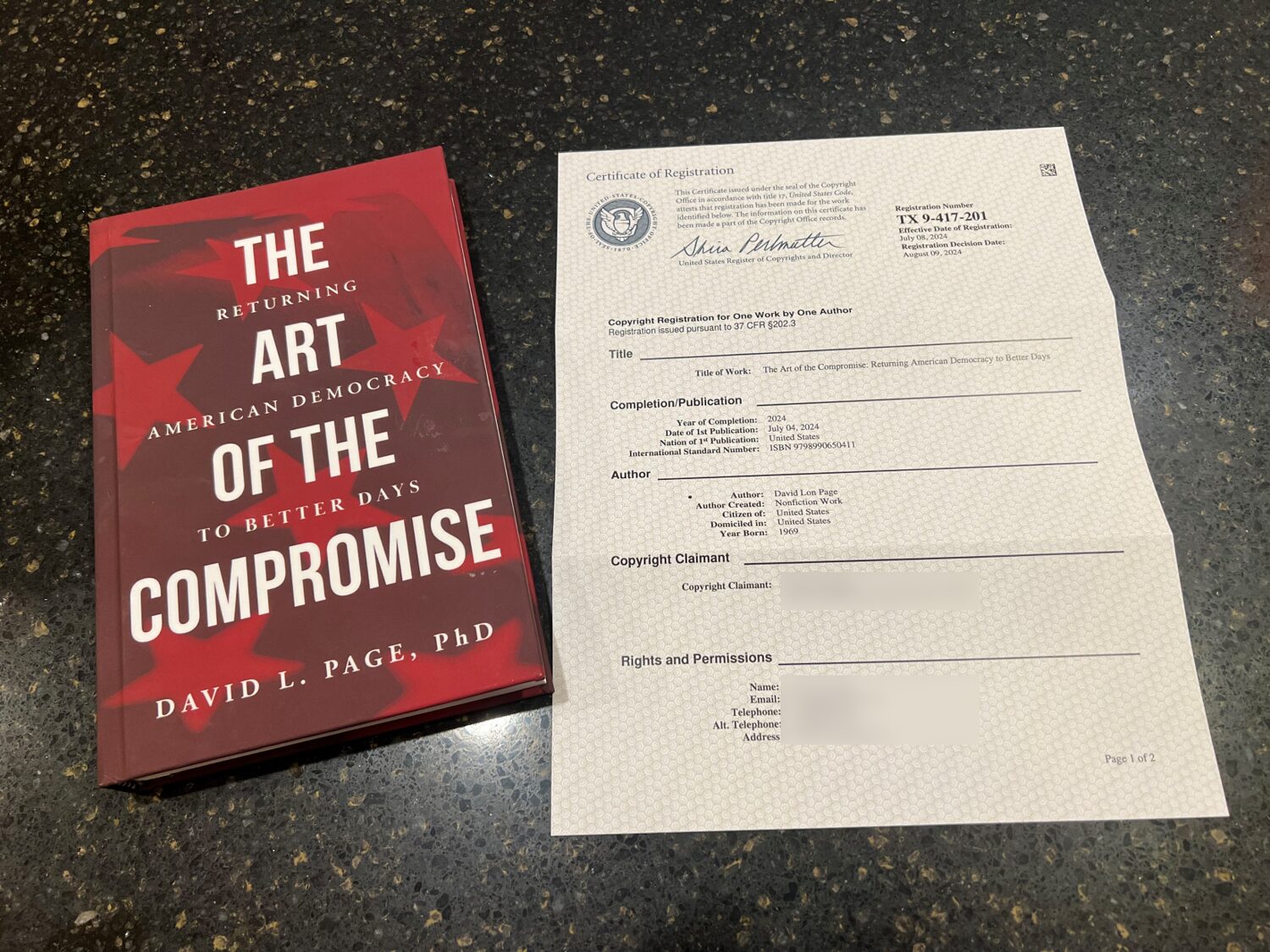

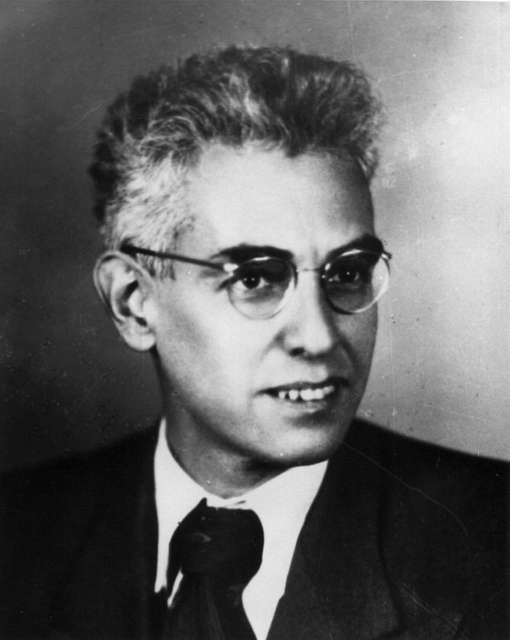

To understand this paradox, we must revisit the case of Solomon Shereshevsky—”S.”—a man with extraordinary memory. Documented by pioneering neuropsychologist Alexander Luria in The Mind of a Mnemonist (1968), Shereshevsky could recall 70-digit numbers after a glance, recite poetry in foreign languages minutes after reading, and remember vivid details from decades earlier.

But this superpower came at a devastating cost.

Photo of Soviet-era Psychologist Alexander Luria.

Shereshevsky’s world was overwhelming. He couldn’t forget anything—not a face, not a word, not even a tone of voice. His mind was flooded with details, and the simplest abstractions baffled him. Faces, for example, became unrecognizable if a single detail changed. A metaphor like “I could eat a horse” left him confused. How could someone possibly want to eat a horse?

He couldn’t generalize, couldn’t abstract, couldn’t let go. And that made life deeply difficult. Eventually, the burden of his memory drove him to alcoholism. He died in obscurity, his brilliance reduced to a sad footnote—rescued only by Luria’s pen.

Face sequence of the same person over different periods. Photos by Paul Downey, CC BY 2.0. Mr. S. would struggle to recognize these images as the same person.

The Perils of a Digital Memory

Our society is becoming like Shereshevsky.

In the pre-digital age, forgetting was built into the human experience. We relied on imperfect memories and oral histories. Stories faded. Embarrassments passed. Privacy was possible.

But with the invention of photography—and later, the internet—we began building a world that doesn’t forget.

An original Kodak “Snap Camera,’ serial number 540, ushered unwittingly the age of privacy—or lack thereof. Image credit: National Museum of American History. CC BY-NC 2.0.

In his book The Future of Reputation, Daniel Solove recounts the story of “Dog Poop Girl,” a young woman in South Korea publicly shamed when photos of her refusing to clean up after her dog on a subway went viral. Her identity was revealed, her reputation destroyed, and her life derailed. One moment endlessly replayed. No second chances.

This is the Luria Paradox in action: a society with perfect recall that cannot move forward. Just as Shereshevsky was trapped in a loop of vivid, unfiltered memories, we too are stuck reliving the same viral moments. We struggle to abstract, to forgive, to forget.

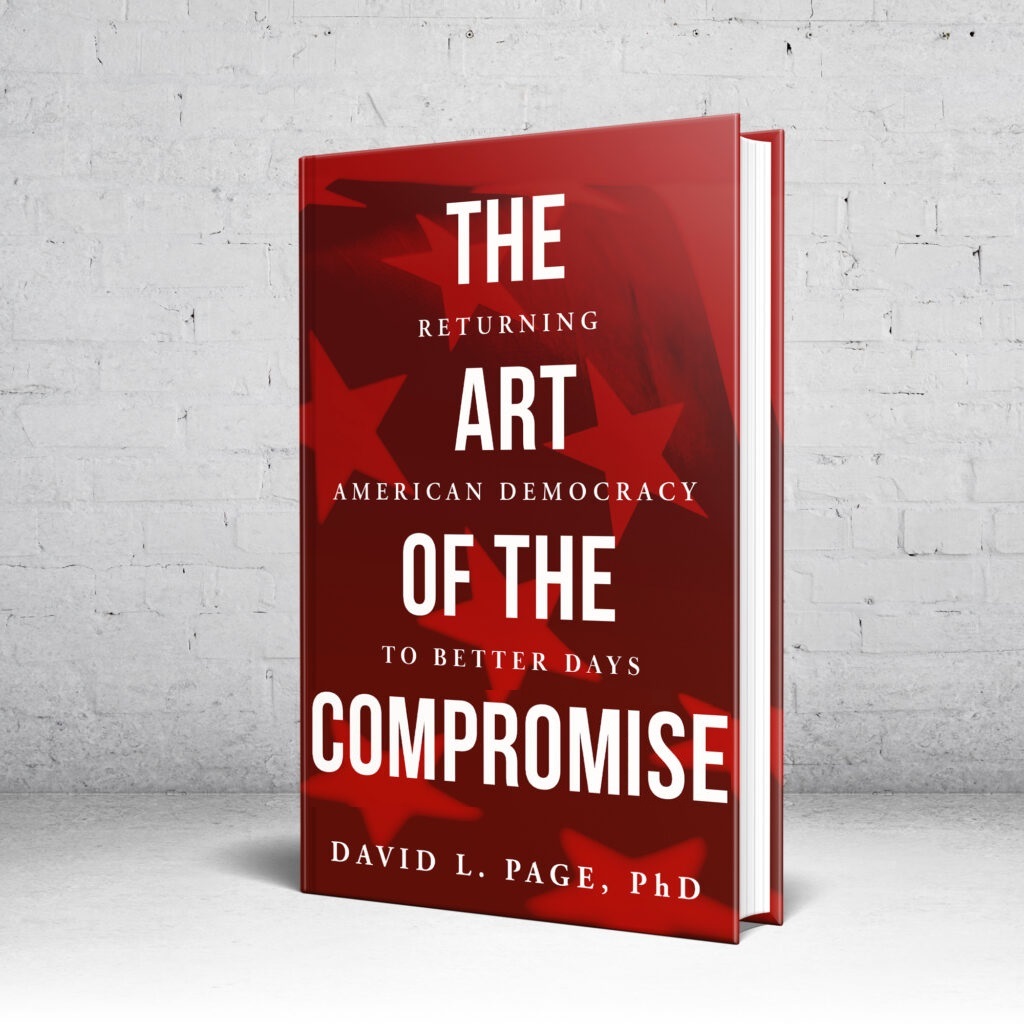

Politics in the Age of Perfect Memory

The Luria Paradox is reshaping our politics, too.

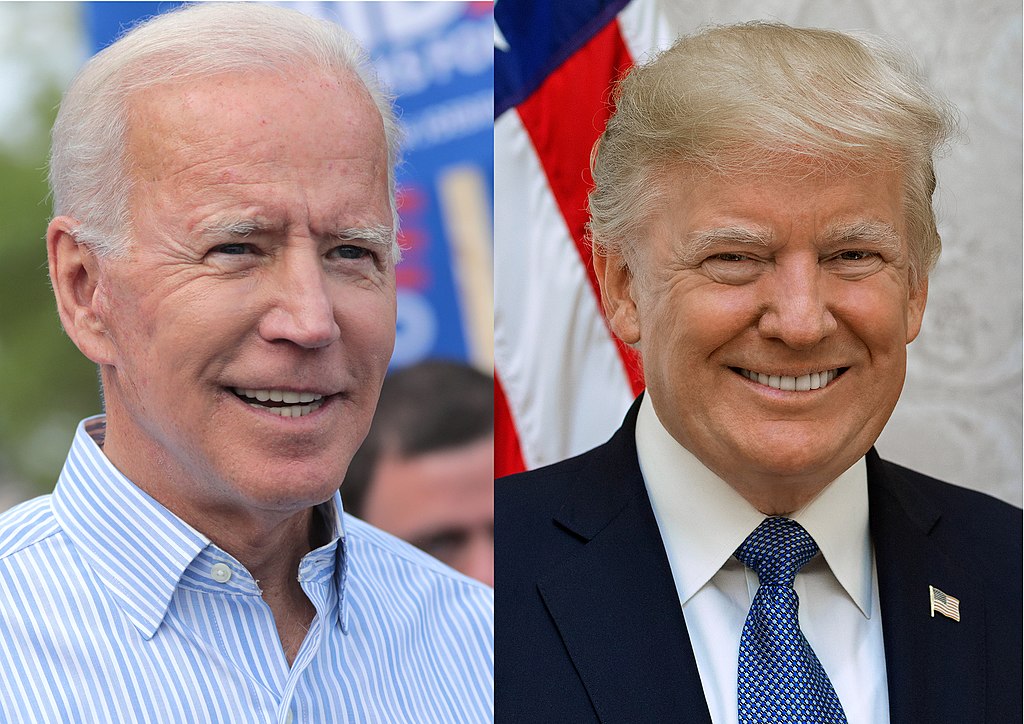

On one end, we have politicians like Joe Biden—careful, measured, and often unremarkable. In a world where a single slip-up becomes a permanent meme, cautiousness becomes a survival strategy. Biden seems paralyzed by the fear of being the next Dog Poop Girl, stuck in the amber of scrutiny.

On the other end is Donald Trump—a man who barrels through scandal with such volume and velocity that nothing sticks. He overwhelms the collective memory with audacity. His leadership style is less about avoiding mistakes and more about flooding the system with them.

Biden and Trump are likely the best options in a digital world that can never forget. Joe Biden: Gage Skidmore from Peoria, AZ, United States of America (source: Joe Biden); User:TDKR Chicago 101 (clipping)Donald Trump: Shealah Craighead (source: White House)Сombination: krassotkin, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

These two extremes—the risk-averse and the reckless—are the political symptoms of a society that no longer forgets.

Neither model is healthy for democracy. We need leaders who can grow, experiment, and fail—without being frozen by the unblinking digital eye or adopting a nihilistic bravado to survive it.

Reclaiming the Right to Forget

In Permanent Record, Edward Snowden makes a striking point:

“Saying you don’t care about privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different from saying you don’t care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say.”

Privacy isn’t about secrecy—it’s about the freedom to change, evolve, and recover.

A society that never forgets is a society that never forgives. If we demand perfect transparency from our leaders, if we insist on remembering every mistake, we’ll end up with only two kinds of politicians: those who do nothing and those who no longer care.

We must find a way to forget again—to allow grace, change, and the messy process of becoming. Without this, we doom ourselves to a cycle of frozen memories and stunted growth.

That’s the heart of the Luria Paradox: when memory is too perfect, it ceases to serve knowledge—and begins to destroy it.

Disclosure: ChatGPT edited the original post authored by David Page.